We wear our hearts on our soles. “Shoes are the best indicator of how people are feeling,” says June Swann, a shoe historian based in Northampton, England. To hear Swann tell it, you can chart the rise and fall of prosperity from the elevation of a heel; hear the distant rumblings of war in the configuration of a toe; measure social change by the thickness of a sole.

Every shoe tells a story. Shoes speak of status, gender (usually), ethnicity, religion, profession, and politics (the Russian writer Maxim Gorky said a strong pair of boots “will be of greater service for the ultimate triumph of socialism than . . . black eyes”). Last, far from least, they can be drop-dead gorgeous.

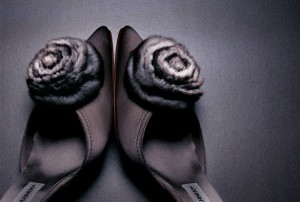

“It will never sell in London,” Manolo Blahnik sighs, cradling the silk-and-fur mule. “You know. The British. Animal rights. No foxhunting. No shooting birds. It is crazy.” He huffs. Looks hurt. “They won’t buy this shoe, but—they’ll eat rabbits and poor little animals like that.” There is a giggle like the splash of water in a fountain.

Politically correct or not, there is an irresistible urge to pet this shoe; put it on a leash; take it to bed. It is a Manolo Blahnik high heel, and for more than 30 years, Blahnik has designed shoes that are the accessory to a fairy tale: Shoes made of rhinestones, feathers, sequins, buttons, bows, beads, grommets, rings, chains, ribbons, silk brocade, bits of coral, lace, fur (from farm-raised animals, he adds), alligator, ostrich—everything, perhaps, but woven unicorn forelock.

Blahnik is a rara avis himself—an exotic hummingbird. He speaks in exclamation points. He will not sit still. He jumps up from the chair in his office with walls of dove-wing gray on King’s Road—a bird flushed from cover. He exclaims, enthuses—he is all flourishes, rococo gestures, exquisite manners; impossibly elegant, spotlessly groomed with silver hair combed straight back. There is the glen-plaid double-breasted suit, a purple-yellow-and-white knit tie, and—peeking out from the sleeve of a blue cotton shirt—a red crocodile band attached to a gold Swiss watch. The shoes are size 42 1⁄2 buckskin oxfords made for him at his factory in Milan. “I dress like a banker,” he says when asked if the suit is custom-made. (It is.)

The story has been told before, “but”—he shrugs—”it is the only story I have.” After studying art and literature in Geneva, Blahnik fell in with the fashion crowd in New York and met Diana Vreeland, the legendary editor of Vogue. Vreeland looked at his sketches. Do accessories—pretty little things, she said airily. And so he has. A “Manolo” is the Sex and the City shoe (in one episode Carrie realized she could have made a down payment on a New York apartment for what she spent on shoes), a generic term for a high heel, and the inspiration for Madonna’s remark that his shoes are as good as sex, and “last longer.”

Ladies, listen. When Manolo dies, there will be no more Manolos. There is no heir or protégé. No big luxury goods conglomerate like LVMH waiting in the wings. No. No. No. When Blahnik has gone to that great shoe box in the sky, Manolos are finished. Done. Not for Manolo Blahnik a label without the real person behind it. Not like Christian Dior (died in 1957), Coco Chanel (1971), or Roger Vivier (1998), labels that survive under the aegis of others. Consider Salvatore Ferragamo (died in 1960) whose dynasty rests in the hands of his children and grandchildren. Blahnik darts off to fetch a photograph of the Italian who immigrated to California in 1914 and became shoemaker to the stars. The photograph shows Ferragamo, his big, broad face and broader smile, surrounded by the lasts of the actresses—Greta Garbo, Rita Hayworth, Sophia Loren—for whom he made shoes. “Look at that face,” he says. “He is a peasant! Brilliant. But a peasant!”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.